升中派位2024|即睇全港18區英中學額分布

2024-04-12 08:30

英國升學|調查:逾三成家長冀讓子女赴英升學 平均預算360萬元 成本逐年增10.7%

2024-04-23 21:00

DSE開考懶人包2024|核心科/選修科精讀備戰攻略 + 解構扣分/DQ陷阱 + 惡劣天氣安排

2024-04-03 06:30

李建文 - 校園欺凌零容忍|牆角寒梅

9小時前

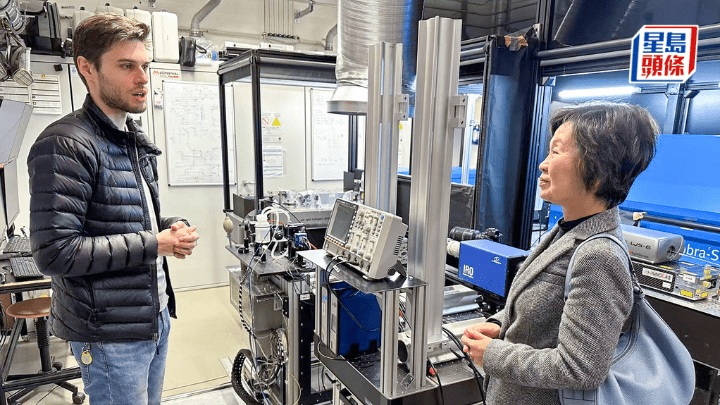

蔡若蓮訪德應科大 了解職專教育發展

10小時前

趙曾學韞小學派「0班」申辦私立小一獲批

11小時前

鎂光燈下成長的童星兄弟黃梓樂、黃梓賢 拍戲也是學習:訓練記憶力與時間管理

2024-04-23 17:27

親子旅遊2024︳東莞觀瀾湖酒店人均低至$212 開放訂5.1/母親節/端午節假期 附2大親子好去處

2024-04-23 16:37

緊貼2024文憑試|分析中文卷一閱讀篇章(之二)

2024-04-23 14:00

親子優惠︳海洋公園萬豪酒店自助餐低至$271歎蟹腳/燒西冷 晚餐任食波士頓龍蝦、母親節送甜品

2024-04-23 12:24

凌婉君 - 製造成功對小孩的重要|家長教室

2024-04-23 12:01

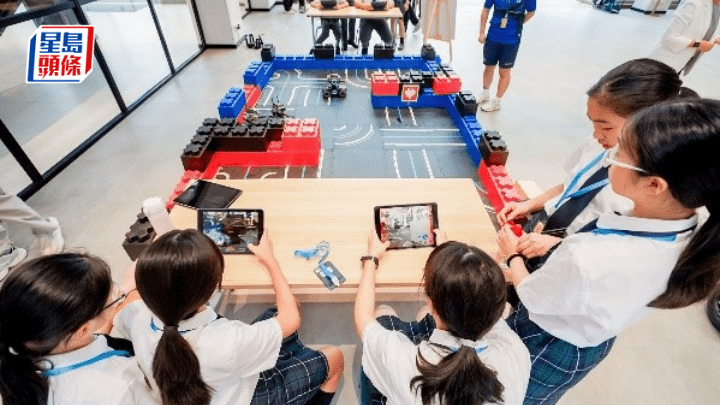

中華文化護照計劃20中小學參與 校長:可增潤公經社科及人文科

2024-04-23 11:44